|

If you look at the current landscape of throwing in the United States, you are quick to see that there are many up-and-coming throwers currently competing at the collegiate level. In the opening week of the outdoor season, Magdalyn Ewen, competing for Arizona State, broke the women's American collegian hammer record with a throw of 72.71m. There have been countless performances, such as this one, this past season. Another young and up-and-coming thrower is Mckenzie Warren, throwing for Concordia University. She broke the Division II Indoor Shot-Put record with a throw of 17.62m. With so many great performances coming this 2016-17 season, the researcher in me is thinking, "What type of support system(s) do throwers like Magdalyn and Mckenzie have in place that have allowed them the opportunity to reach the pinnacle of throwing in their respective events (Hammer & Shot-Put)?" A great opportunity was presented to me the other day when Sean Donnelly, an up-and-coming American hammer thrower, invited people to ask him questions for Q&A he was conducting with fellow thrower Cullen Aubin. For those of you reading, you know I couldn't resist the temptation to ask Sean this question, "What people have contributed most to your post-collegiate success so far?" Thank you Cullen for selecting my question. Thank you Sean for answering. You can find his answer below. You can find Cullen's Youtube page below. For the current collegiate and post-collegiate throwers out there, in what ways do you feel your support system has contributed to your throwing success? Are there specific people that assisted you early on in your throwing career that paved the way for you? Do you feel it was the physical environment and location? Have training partners played a role in your success?

Like I mentioned on Sean's Youtube comments, I believe it is important for throwers to share their message's for others to hear. Throwing is a relatively obscure sport, however sharing your why and putting yourself out there can generate a following, or social media support system, that gets behind you and is interested in your throwing success. It's difficult to support someone if you don't know that much about them, what they like and don't like, and do what they do. As always, thanks for reading. Please share your comments below, on Facebook, or even on Instagram. My best, Charles

1 Comment

One of the best decisions I ever made was to get into coaching. In all honesty, it really happened by chance. Mid-way through my senior year at SUNY Fredonia, our head men’s track & field coach notified the athletic director that he would not returning the following year. Our men’s head coach was also my throwing coach. That fall semester, our interim head coach asked me if I would be interested in coaching the throwers. I had coached recreation soccer teams before, so how hard could it be to coach the throwers I was previously teammates with? I learned early on that it wasn’t going to be as easy as I perceived it to be. 1. You don’t know what you don’t know I really had no idea what I was doing for the first couple months I was working with our throwers. I had a basic idea of what I wanted them to do in the weight room. Up until that point in time, our previous throwing coach never really gave us a weightlifting program. He encouraged us to squat, bench, and deadlift. I thought I knew what I was doing, but I was wrong (insert picture of first training program here). Throwing wise, I thought I knew how to teach throwers how to throw. I understood basic weight throw and shot-put concepts. I implemented what I had learned from my previous three throwing coaches. We used a lot of chairs and tape while completing turning drills to perfect our weight throwing technique. We also ran a lot of stairs. My advice to new throwing coaches—seek out a mentor. Someone you respect and would like to learn from. Coaching throwers is difficult, even if you have previous throwing experience. I wish I would have sought out the assistance of other coaches sooner than I had. 2. You are Coaching Your Athletes, Not Your Friends Coaching my previous teammates was not all it was cracked up to be. I thought it was going to be pretty easy. I was mistaken. One thing I did not take into consideration when I accepted the throwing coach position was the previous history I had with the athletes that were now in my care. It’s probably something most people don’t think about when they accept a position as an assistant coach at the school they had just graduated from. You may go from partying together, to training together, and to complaining about the coaching staff together to now trying to lead and coach these individuals. I found it to be a difficult transition because I thought I was going to be treated like their coach. I don’t believe I was at first. I think we were more friends than coach and athletes. This was my fault. My advice to new throwing coaches—establish expectations with your athletes. Whether you are coaching athletes you were previously teammates with or not, establish clear coach-athlete expectations. They need to be enforced. When things get blurry, it isn’t only bad for the coach, but just as bad for the athletes as well. 3. Respect is Earned, Not Given It was my assumption that the throwers I had previously been teammates with were going to treat me differently now that I was their coach. Well, you know what they say assuming things…We had a couple of freshman throwers that joined my first season, 2004-2005. We also had some first time throwers join our team during the spring semester. The transition for the new throwers and myself was fairly seamless. They knew that I had spent the previous four years as an athlete at SUNY Fredonia. They didn’t see me as their teammate, so things went fairly well. Establishing the coach-athlete relationship with my returning throwers was a bit difficult. We had some issues maintaining accountability with getting to the weightroom and communication if someone was going to be late or miss practice. You see, twelve years ago most people did not have cell phones. It was much more difficult to communicate, especially if it was expected that you were going to be someplace, but then not show up. Now, if my athletes meet with a professor or their work groups after class, I get a text message letting me know that they will be a couple of minutes. That wasn’t the case back in 2004. I had to meet with some individuals on a couple of occasions to remind them that they were the team leaders and needed to set a positive example for their less experienced teammates. After our initial meetings, the season went on much more smoothly than it probably could have been. My advice to new throwing coaches—do not assume your athletes will respect you from the first day of practice just because you are their coach. Establish consistency and routines that will set the tone for your season. Athletes can easily tell if you are playing favorites or not being honest with them. Maintain open lines of communication, and make sure to discuss issues immediately when they arise. Do not let things fester because the situation may get worse. Above Left: Jen and I at Outdoor SUNYACS where we both won the hammer (April, 2004) Above Right: Jen, Tim, and I at an Outdoor meet at the University of Buffalo (April, 2005) 4. You Can’t Judge a Book by it’s Cover This is most certainly the lesson I carry with me into every new season. One of the best throwers I have ever coached came out for the team in January, 2005. We’ll call this thrower Claude. At the time, Claude stood about 6’3” and weighed maybe 200lbs. He approached me at one of our practices and told me he wanted to be a thrower. I said that it would not be a problem. Claude told me that he had never thrown before, but was a member of his high school Cross Country team (great). After a couple days of learn-to-turn, I told Claude to take 100 hammer turns a day before he started throwing. I gave him a hammer, showed him with line to turn on, and just left him there. I didn’t watch his turns, form, technique, or anything. That progressed for most of that first season. Claude threw at the Indoor State Championships, throwing just over 40’ in the 35lb. Weight Throw. That following season, Claude was like a man on a mission. He followed the training program over the summer, and came back ready to compete in 2005. And compete he did. Claude scored at the Indoor SUNYAC and Indoor State conference championships in the 35lb. Weight Throw. He finished that season ranked 9th all-time at SUNY Fredonia with a throw of 51’. He also scored at the Outdoor SUNYAC and Outdoor State conference championships in the Hammer. He finished the season throwing over 50m (167’), and was ranked 8th all-time at SUNY Fredonia in the Hammer Throw. My advice to new throwing coaches—you never know what kind of talent you have on your roster. I really didn’t pay much attention to Claude when he started throwing for us at SUNY Fredonia. He turned out to be one of the best throwers I have ever coached. His work ethic and determination could not be surpassed. It was as though he willed himself to success. Now, I welcome anyone that is interested in throwing. As a coach, you just never know how someone may take to the Hammer, Weight, Discus, or Shot-Put. I pay much more attention to new throwers than I did my first year at SUNY Fredonia. Over the course of four years new throwers may develop into competitors that may score or even win conference championships. You just never know. 5. Think About a Philosophy—What Type of Coach Do You Want To Be I think it is clear to those of you still reading that I really didn’t have much of an idea as to what I was doing. I admit that I was not that great when it came to organizing practice, tailoring programs to individuals, and thinking big picture. I was mostly focused on being just a couple of days ahead of my kids. Before I have any inkling that I would be coaching, I accepted a full-time teaching job and was enrolled in graduate school at SUNY Fredonia. Many of my graduate course professors were open to me completing assignments about coaching leadership, and not always about school leadership. One of my curriculum and instruction courses was focused on developing a curriculum plan and map for any subject of our choosing. Rather than write about teaching, I wrote about throwing programs and the type of coach I wanted to be (insert picture of that binder here, if I can find it). I’ve always had the philosophy to give my throwers autonomy in a lot of things that directly have an effect on them during the season-practice time and lifting time. One of my throwers at SUNY Fredonia my first year was a senior, and was student-teaching. She could not make our 3pm start time because she was still in school. I tried being as flexible with her as I could in order to ensure she was given equal practice time. That worked because of the expectations we had set with all the throwers (see #2 and #3). The same went with lifting. A majority of the athletes I coached were education majors. Their schedules were all the same, so they lifted together. For some of the other throwers I coached, their schedules were much different. Some had all evening classes, some had internships, and some had jobs. I spent more time at SUNY Fredonia my first year than I probably did honing my teaching skills. That was my philosophy. I wanted to provide all my throwers with equal time that met their needs. I also wanted to work with my throwers to make them part of the process. They took ownership over our practice times and rarely missed anything because I allowed them to be part of the process. My advice to new throwing coaches—begin to develop a coaching philosophy sooner than you think you need to. Whether you are coaching high school, college, or post-collegiate athletes, make sure you stand for something that you are passionate about. Are you going to allow your athletes some autonomy with schedules, is it always your way or the highway, or are you going to be someplace in the middle? Figuring that out will ensure to make your start to coaching smoother and more efficient than if you don’t have a plan for yourself and how you want to lead the athletes in your care. Tim, Jen, Meredith, Claude, and I at Outdoor States (May, 2005)

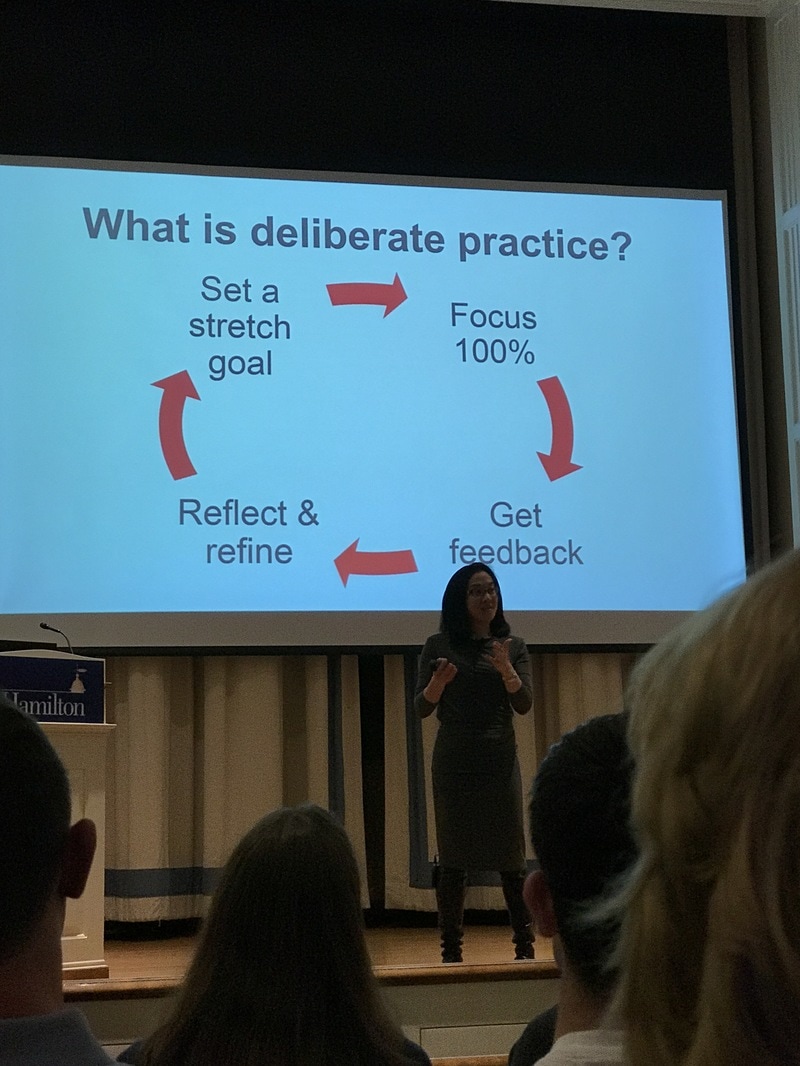

I just got back from the ECAC Division III Indoor Track & Field Championships held at Ithaca College. Besides being a championship meet, the ECAC meet can be considered a last chance qualifier for DIII Indoor Nationals for teams on the east coast. In order to compete at this meet, you need to meet specific standards across all running, jumping, and throwing events. During a break in the competition, a few coaches and I took advantage of the coaches hospitality room, had a great lunch, and engaged in some pretty good conversation about what it takes to throw far. Not just throwing far in college, but throwing far after college as well. Dr. Angela Duckwork with two of her students at Hamilton College, February 21, 2017. Photo credit Charles J. Infurna. One of the coaches, a high school chemistry teacher and coach of over a dozen All-American throwers at the DIII level, brought up the topic of deliberate practice. Below you will find Angela Duckworth's definition of deliberate practice. Dr. Angela Duckworth speaking at Hamilton College on 2.21.17. Photo credit Charles J. Infurna. If you have not had a chance to read Angela's book, I highly encourage everyone to do so. An easy book to read with limited psychological jargon, with great insight on what variables need to be present in order to be considered a gritty person. As the picture suggests, there are four steps to deliberate practice, discussed almost verbatim today at lunch. Step #1: Set a stretch goal Now, in Angela's talk a few weeks ago, she spent a lot of time talking about stretch goals. She discussed the notion that stretch goals should be realistic, and not so far-fetched that they could never possibly be accomplished. For example, if you are a male 40' shot-putter your freshman year of college, it may not be that realistic for you to set a stretch goal of winning the following season's national championship. A more realistic and manageable goal might be to throw 45' the following season and score in the conference championship. I spent a great deal of time at the beginning of the this season meeting with my athletes to discuss their goals. I believe it is important for coaches and athletes to have these types of conversations not only at the beginning of the season, but throughout the season. You may hit that 45' throw in the first meet of the season. Now you can have a conversation about next steps/goals for the remainder of the season. Step #2: 100% Focus In my humble opinion, I believe this is the most difficult step in the deliberate practice process. For those of you reading this, you may coach high school or college athletes. Therefore, we coach athletes that are between the ages of 14-23. No offense to any athletes in this age group, but some of you can be easily distracted. None of my throwers bring their cell phones into our practice racquetball court. This eliminates the potential distraction of checking their latest Snapchat or Instagram comment. It is important to stress to our athletes that from the time they begin practice until practice is done, that they have their minds on practice. I see it pretty much everyday with my athletes. They just came from class and found out they did poorly on a test. Or their boyfriend/girlfriend didn't text them back in 10 seconds (insert sarcasm here). Believe me, I understand that. However, it seems that some athletes still have difficulty with focusing on something. I have tried implementing a one cue rule for myself. Rather than tell my kids two or three or four things they didn't do well, I have made it a goal of mine to only tell them to focus on one thing. Get that thing right, then we move onto the next thing. Some athletes hear the same thing for two or three weeks. It is much easier to focus on one thing, than try to focus on multiple things at the same time. Step #3: Get Feedback In some cases, this step may be the easiest for coaches and athletes to work with. Hoping your coaching relationships with your athletes are healthy and open, this should be an easy step to grasp. It is important for us as coaches to provide our athletes with honest and constructive feedback. Try to emphasize the positive while working together on the negative. I elicit feedback from my athletes as well. Now, I don't ask them how every practice went, but I do want to know what cues work better for them than others. I try not to provide a lot of feedback at meets. By meet time, everything should be pretty much worked out. Yes, we do encounter some things at meets, and we adjust. I've noticed that the coaches that speak to their athletes the most at meets, especially big meets like nationals, don't tend to fare as well as other athletes that have minimal contact/conversation with their coaches. You are already at nationals. Focus on the positive, provide healthy feedback, and know what cues work best for your athletes. Hammer practice with Luis Rivera before DIII Outdoor Track and Field National Championships, May, 2016. Photo credit to Nazareth College. Step #4: Reflect and Refine This may be the most crucial step in the deliberate practice cycle. For the coaches reading this article, how often do you sit back after a meet and reflect on how the meet went? Reflecting on track meets has probably given me more grey hairs than anything else in my life. Do you reflect on goals with your athletes? As coaches, are you open to receive constructive criticism and feedback from your athletes? I usually only have this type of conversation with my athletes a couple times a year-once after the indoor season and then before they go home for the summer after our outdoor season. I believe it is important for me to know what I need to work on in the off-season to become a better coach. Just as we expect our athletes to complete our conditioning and training programs while they are home for the summer, we as coaches should work on things that can help us be more efficient coaches. I have seen many posts this year on Instagram or videos on YouTube with coaches sharing how they work on their craft over the summer. Some coaches read. Others attend conferences and workshops. What do you do to help yourself grow as a coach? As always, thanks for reading. If I missed anything, please let me know. Leave a comment below. My best, Charles Two of the books I've read this year. If you have not had the chance to read any books by Jon Gordon, The Hard Hat would be a great one to start with. Champions is a great book that provides interesting insight into the development of Olympic Swimmers. Dr. Daniel F. Chambliss is a professor at Hamilton College, located in Clinton, NY.

|

Dr. Charles InfurnaCharles Infurna, Ed.D., is the owner and lead coach of Forza Athletics Track Club. Dr. Infurna has coached National Record Holders, National Champions, All-Americans, and Conference Champions at the Post-Collegiate, Collegiate, and High School level. Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed