|

Yesterday I received one of the best compliments I have ever received as a coach. This compliment was very special. It was extra special because it wasn’t about me. It was about my throwers. On two separate occasions during a very soggy and damp meet at St. John Fisher College, coaches from different colleges complimented me about my athletes.

One came after the women’s hammer. Yesterday, Kaela (our freshman thrower) improved her hammer personal best by 5m. It was her fourth time this season throwing the hammer, she is still learning, so an improvement of 17’ isn’t uncommon. However, the compliment wasn’t about her performance. It was about her heart. The coach told me that during the lead up to the hammer, and during the competition, he didn’t hear her complain or say any negative comments about the weather. It was raining, not very hard, but hard enough to cause other people to have off days. He did compliment her (us) on her performance, but that wasn’t the primer of the conversation. He told me that she throws with heart! I told him “thank you”. I also said that I wish it was something that could be coached. He gave me a puzzled look. I’ll get back to this later. A few hours later, during the women’s shot-put, I was talking to another coach about how well his season was going. I complimented him on how well his athletes’ have been performing during the season. I asked him how he arranged his practices, trying to figure out how many practices he held during the day to ensure everyone got enough throwing reps. He told me he only has one, very long practice a day. Lasting about three to four hours, his athletes cycle into practice after they are done with class. That is a different strategy than some of the other coaches I’ve discussed practice times with. As we were discussing his athletes and what they were doing after graduation, he said he didn’t know. Similar to my previous conversation from a few hours ago, he told me that his kids don’t have the same heart that my kid’s do. I looked at him puzzled. “What do you mean”, I responded. He told me that they don’t have the same heart that Luis and Tyler have. Again, I said thank you. We continued on with our conversation until Kaela finished throwing the shot-put. I’m not really sure what to say. I’ve written about it before. Now, maybe it is something that I haven’t figured out yet as a coach, but I maintain that one of the traits a coach cannot coach is an athlete’s heart. It is difficult for me to define. I can tell you what I don’t think it is. Having heart is something different than being motivated, having a desire to succeed, or an excellent work-ethic. It is unlike being truly dedicated to your craft, or being deliberate about practice, and not the same as having a do what it takes attitude. Having heart is something different. It is a willingness to overcome all obstacles put in your path. I say willingness because not all athletes are willing to attempt to overcome adversity and barriers. Some athletes let those obstacles overpower them. They are not willing to put forth the time to “climb the mountain” if you will. Tyler and Kaela do indeed have heart. They have overcome more adversity in their very young lives than most people. I’m willing to guess more than people their age. They inspire me. They inspire me to be a better coach. A better father. A better husband. A better person. Thank you for a rewarding and inspiring 2017-18 season. My word for the year was resiliency. To be more resilient in difficult times. It is only fitting that you, Tyler and Kaela, epitomized what it means to be resilient.

0 Comments

The other day I had the great privilege and honor to have lunch with one someone I have a great deal of respect and admiration for, Dr. Dan Chambliss. I’ve met with Dr. Chambliss on two previous occasions. In our previous meetings I felt a bit star struck and ill prepared for our conversations. I was more than ready today.

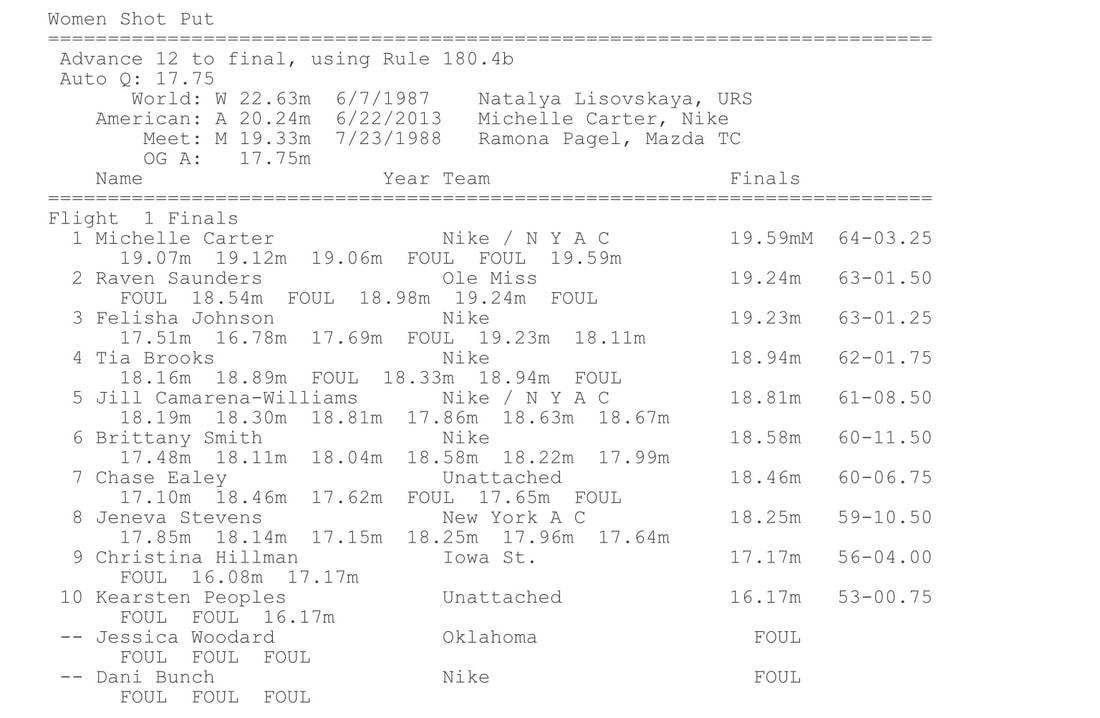

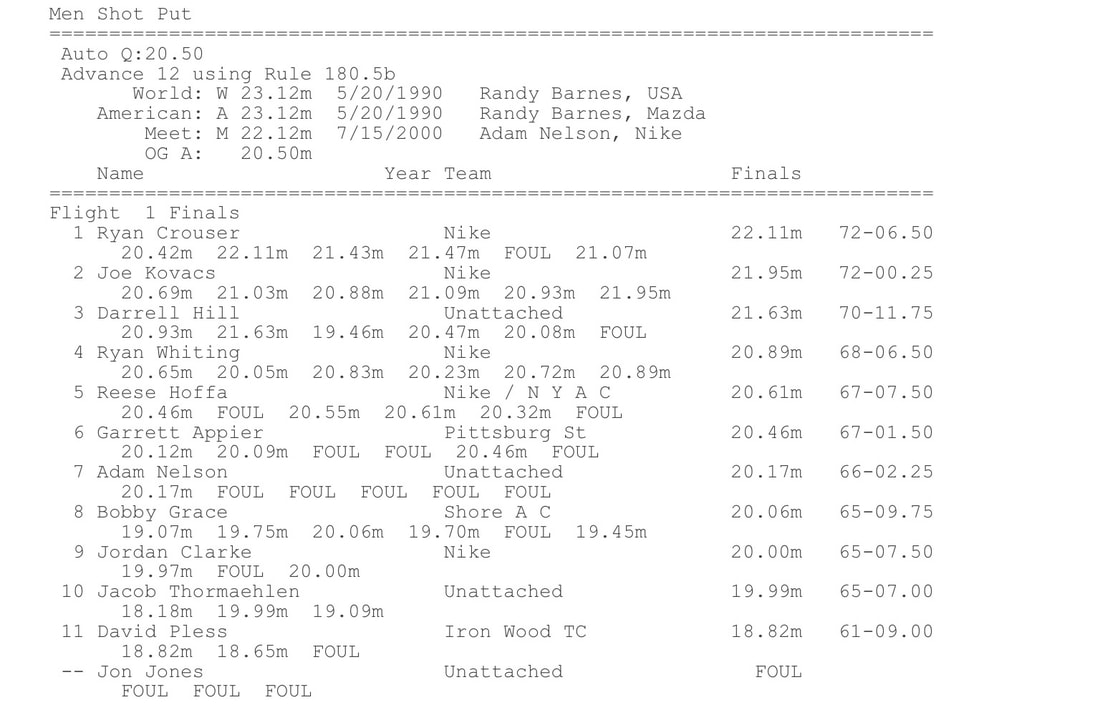

A couple of weeks ago I Tweeted a quote by Dan taken from his book about developing Olympic swimming champions. To my surprise, he suggested we get together for lunch. I wasn’t going to let this opportunity pass by. I drove two hours from Rochester to Hamilton to discuss mundane things. I still haven’t figured out why his book on Olympic swimmers fascinates me so much. I never swam competitively. I took swimming lessons until 8th grade, never competed in a race, and yet I find the notion of mundanity to interesting and mysterious at the same time. The mystery lies in the mundane. The most dazzling human achievements, as Dr. Chambliss states, are in fact the aggregate of countless individual elements, each of which is, in a sense, ordinary. And yet, these daily and ordinary tasks are the building blocks for future success. Similar to the construction of a house analogy, you need to have a strong base in order to support the weight of the house, we need to complete ordinary tasks on a daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly basis in order to establish a firm, supportive, and resilient base to achieve athletic success. Much like the swimmers in Mission Viejo, California in 1984, their “secret” lay in their completion of daily tasks that others may have found boring, not important, or simply not willing to do. It takes a dedicated, motivated, and gritty person to get up every morning and swim six miles before going to school, and then coming back later that afternoon and doing it again. Mastering technique. Mastering turns. Mastering every little aspect of swimming. Being deliberate before deliberate was really researched by Dr. Ericsson and Dr. Duckworth. Everyday. 365 days a year. For multiple years. Maybe dedicated isn’t the right word. The roots seep deeper than sheer dedication. As I mentioned, I was prepared today. Still a little star struck. I mean, it isn’t every day that you get the chance to eat lunch with one of the most respected and often cited Sociologist of the last 30 years. Our conversation today, much like our previous two meetings, began with me asking Dr. Chambliss questions that he has probably been asked hundreds of times before, especially about his Olympic swimming. Today, however, I asked him a question that he probably hasn’t been asked as often. I asked him if his theory of mundanity could be replicated in 2018. I could tell by the look on his face that this probably wasn’t something he has often been asked. Could the mundanity of excellence theory be tested with Olympic throwers? We spent a great deal of time talking about coaching; philosophies, how to work with individual athletes, expectations, and goals. My biggest takeaway from today is this-it is ok to coach athletes, in my case throwers, who do not have the drive to be Olympic champions! Let me explain. I shared a situation I previously had with an athlete. This particular athlete shared his very lofty goals with me. However, the athlete did not complete the tasks necessary to achieve their goals. In fact, the athlete didn’t do much of anything that would have led to achieving those goals. They failed to live up to their end of the stated goals. I told Dr. Chambliss that I spoke to the athlete about it, in which I shared that they did not complete any of the minimal tasks necessary to achieve their goals. Dr. Chambliss told me I handled to situation poorly. He shared a similar story with me. One in which he wanted the athlete to perform up to a certain standard and expectation. One in which he, as someone told him, wanted more than the athlete. Instant light bulb moment for me. I have had other coaches share similar stories with me, but it didn’t click until today. He told me that it was ok for the athlete to not do what they needed in order to achieve their goal. That, in the bigger picture, wasn’t really a big deal. He said, rather than try to focus on the one athlete, create a culture that is built to support the bigger goals of the athletes that are doing everything in their power to achieve them. It is ok to not reach your goals, he told me, but that it is also ok to focus my attention on the athletes who are working towards their goals. He explained that because he wanted the see the athlete succeed more than they did, it in fact negatively affected their relationship. The athlete, in this case a 12-year old female swimmer, who had all the talent in the world, didn’t like to work hard. Thus, in her case, her genetic talent alone was going to carry her only so far. Unfortunately, she ended up quitting a couple years later. He wanted for her to be successful more than she wanted the success for herself. An a-ha moment for me. When athletes and I discuss their goals and commitments to throwing and track & field at the beginning of the season, we discuss them together. It is a partnership. We need to meet each other half way in order for the success to happen. In the past, much like some other coaches out there, I’m guessing that they may take it personally when an athlete doesn’t achieve their goal. I have. I do. I have always felt that it was my ultimate responsibility when an athlete didn’t accomplish something. Regardless of what was going on in their life, I thought I could will them to achieving what they wanted to achieve. Most recently, that hasn’t been the case. Now I know why. It is ok to set a goal and not achieve it. Maybe their judgement was clouded. Maybe the athlete thought they wanted to achieve that specific goal, until they realized that maybe they weren’t willing to do what it took to actually achieve it. Maybe I shouldn’t take it personally anymore. We also talked about life and research. We talked about the life/research balance. We discussed future research. We discussed mundanity. I asked Dr. Chambliss if I could start researching mundanity. Mundanity specific to throwing. I couldn’t think of a very clever way to do so besides just asking. He said yes! I think part of my fascination comes from the fact that I know Olympic throwers, have their contact information, and have competed against them at one time or another. You can’t do that with the four major sports. I’ll probably never catch a pass from Tom Brady, or ever face Justin Verlander while standing in the batter’s box. I can say that I competed in many hammer competitions with multiple time Olympians (AG Kruger and Kibwe Johnson). Their success isn’t a mystery. There isn’t really a secret. They were able to sustain their success. That is what I’m most interested in learning more about. How are these elite athletes able to sustain their success? Can the mundanity of excellence theory be tested with Olympic throwers? We’ll soon find out! For the third time in the past couple of months I finished the book titled Peak: Secrets From the New Science of Expertise, by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool. Dr. Ericsson is the world’s foremost leading researcher on the topic of expertise. He has dedicated his career on learning more about mastering such fields as number memorization, classical pianists, and classical violinists. More specifically, he often asks how long it takes to reach a specific specialization or level of expertise on the particular field. He is based out of Florida State University. After finishing his book this most recent time, it got me thinking about expertise in throwing. More specifically, do throwers that qualify for the Olympic Games, on average, spend more time training and throwing than their peers who do not qualify for the Olympic Games (specific to throwers in the United States only)? I’ve been thinking about it for a few days, and I think it is an interesting question. Similar to the question I posted above, a very prominent and successful throwing coach recently wrote an article for Track Coach, the journal released by USATF. In his article, Coach Babbitt discussed the notion that the United States has not had recent success in producing Olympic medalist caliber Javelin throwers. We have many American male javelin throwers consistently throwing over 70m (230’), however we have had very limited success in the World Championships and Olympic Games. One of his suggestions to possibly alleviate the United States of their male javelin throwing drought is to keep successful coach-dyads together in the hopes of building upon their collegiate success. Allow them to attend camps and clinics together. Provide them the opportunity to learn and grow together, as a team, rather than only provide resources to the thrower without aiding their coach. Allow them the time to train together, quality training time that is deliberate in nature. That recap may be a little off tangent, but it does beg the question: Do American Olympic Qualifiers spend more time training (hours) on average, than their peers who do not qualify for the Olympic Games? The United States has a rich history of successful male and female shot-putters. Two throwers, Michelle Carter and Ryan Crouser, have recently won World Championships and Olympic Gold Medals in the shot-put. They both come from throwing families. I remember reading about Michelle when she was in high-school, regarded as the future of the women’s shot-put. Similar to Ryan, coming from a family of throwers, he had a great collegiate career before turning professional. I’m willing to take a guess that they, on average, spent more time training than their peers. They had hundreds and thousands of hours of specific throwing training before entering college, and they both achieved great success as collegiate throwers. They are unique, probably not the norm. Michelle’s dad has an Olympic Silver medal in the men’s shot put, and still holds the men’s high school record, having thrown over 80’. For our other American Olympians, have they accumulated the same amount of deliberate practice that Michelle and Ryan have accounted for? I asked an American Olympian this very question-how much time did you spend training before qualifying for your first Olympic games. The response I received was about 2000 hours. The thrower I asked had graduated from college, and the 2000 hours represented two years leading up to his first Olympic games (not taking into consideration his previous collegiate training hours). Breaking it down even more, that is about 1000 hours a year, or roughly 20 hours per week of training (throwing and weightlifting). I’ll get back to this example later. Let’s bring it back to the 2016 Olympic Trials competition. My question is, leading up to the Olympic Trials (let’s say the four previous years), did Michelle, Raven, and Felisha have, on average, more practice hours than their peers that did not finish in the top 3? Getting back to Anders’ study of time spent playing the violin, his study of German violinist found that the students considered to be at the top of their class (having the best potential to earn a chair on a prestigious orchestra) had on average, spent more time practicing their craft than their peers that were considered to not have as great a chance to earn a prestigious spot on an orchestra in Germany. Some students reported having spent up to 8000 hours practicing the violin before they turned 20. Results from the 2016 Olympic Trials-Women's Shot-Put (www.usatf.org) Results from the Men's 2016 Olympic Trials-Shot-Put (www.usatf.org) Now, with our American female shot-putters, I wonder if the same would be said for our three Olympic qualifiers? Obviously training for the shot-put is much more physically taxing on the body, and I wouldn’t think that in the four years leading up to this Olympic Trials that any of our top three women practiced/trained, on average, over 2000 hours. However, I wonder if their average was more than the other competitors?

Similarly, can the same be said for the American male shot-putters? If you look at the finals list, you will see two previous World Champions and Olympic Gold Medalist in the shot-put (Adam Nelson and Reese Hoffa). I’m pretty sure they have accumulated the most training time combined than everyone else on the list’s time put together. Adam and Reese have been on the American throwing scene since 2000, and pretty much made every American male shot-put team that competed in the World Championships and Olympic Games since 2000. When I talk about accumulated training time, I’m referring to time spent really focusing on a specific aspect of throwing and training. The real mundane activities that need to be done in order to put yourself in the best possible position to succeed. A second thrower I asked told me that he spent 14 hours a week focused on throwing and weightlifting. He qualified for the Olympic Games. I’m not saying that anyone who spends XXX amount of time training will automatically become an Olympic thrower. That isn’t the point of the article. It has to be deliberate. It has to be focused upon, not just for the sake of doing it. Your focus has to be deliberate. You need to receive feedback, make changes, adapt, and receive feedback again. Angela Duckworth discussed this in her book Grit. For American throwers however, is there a threshold that gives someone a better opportunity at qualifying for an Olympic Games? In the case of the shot-put, it makes sense that American throwers have accumulated a lot of training time, since the shot-put is contested at pretty much every high school in the country beginning in middle school. The same can be said for the discus, yet we have not had as much recent success in American discus throwing as we have had in American shot-putting. Equal time, therefore, in this case, does not equate to success at the international level. If not time, then what? Ever since my wife and I started dating, she has insisted that I’m a “mark” for famous people. She very often says, “Chuck, they are just people like everyone else. Get over it!” She is right, but I cannot get over it. Before we got married I attended a wrestling show in Buffalo, NY in which I had the chance to meet my favorite wrestler of all-time, Hulk Hogan. How could I not get excited about that?!? Or the time I also met Olympic Gold Medalist Kurt Angle. Again, how can you not get excited about the once in a lifetime opportunity to meet someone who won a gold medal in the Olympic Games. Every time I travel to Ashland and speak with Jud I feel the same way. Nervous and excited. Nervous because Jud is a 4x Olympian. Excited because I can drive down to Ashland and speak with him, or even give him a call. It is just something about the environment that gets my adrenaline pumping as if I was competing again. The sensation occurred more often than I’d like to share, but I guess it is who I am. I felt overwhelmed on more than one occasion when competing against AG Kruger and Kibwe Johnson, both Olympic Hammer throwers. Especially when you immediately follow AG Kruger after he threw 76m, and then the officials have to pull the tape in 50’ for your throw. Or the time I followed Kibwe after a massive throw at Kent State in the 35lb. Weight Throw. I tried following. It didn’t always go well, but I can’t think of many other sports in which you can compete with an Olympian. I felt those same feelings today. Not at a track meet however, but at an Olympic Weightlifting competition. Today I attended the 2018 USA Masters Olympic Weightlifting Championships, held in Buffalo, NY. I definitely marked out in every conversation I had with lifters and coaches from all over the country. One lifter in particular has been a great inspiration to me this year. She is partly responsible for me signing up for my first sprint triathlon. Her name is Veronica Muniz. You never know how first impressions are going to go. The thought of meeting an ‘Instagram’ friend is a little nerve wrecking I must say. What will they be like, will they know who I am, or will they think you are weird for introducing yourself? Veronica far exceeded my expectations. It’s probably because we have a lot in common. Both educators, bilingual, parents, goal-oriented, and willing to step out of comfort zones. Veronica beat me to it though. She began weightlifting only a few years ago. And here she was, traveling all the way from Southern Texas to compete in Master’s Nationals. I’ll let Veronica share her story of how she finally made it to Buffalo. It only adds to her success and accomplishment of medaling today. When I first read of Veronica’s story on Instagram, it caught my attention in more than one way. She is only a couple of years older than me, so when I read that she had just started weightlifting a few years ago I thought, “Wow, that is pretty cool to start Olympic weightlifting a little later than most would start!” She posts videos frequently, making it easy to follow her progress. She slowly was making progress. Then I saw that she entered Masters Nationals. That is when I really thought that I should try something too. Something out of my comfort zone that I’ve wanted to try for a long time. Veronica inspired me to register for my sprint triathlon. Veronica’s focus and drive today was both humbling and inspiring. Inspiring because she registered for and competed in a National Championship event. Humbling because I know how much harder I need to work to reach the level of success she has reached. I am in no physical condition to compete in my age group Triathlon National Championships. I’m 50lbs. over the Clydesdale division (for men that weigh over 230lbs.). I know I would get smoked in that championship. I’m nowhere close to qualifying for it either. After watching Veronica compete today, I have found a new sense of hope and determination about my training, making sure I get all my training sessions in, rest, recover, and embrace the suck! Thank you, Veronica! Veronica, thank you for the picture! Veronica was not the only person that I found inspiration in today. I watched pretty much all the sessions this morning and afternoon. Lifter after lifter stepped onto the platform to give their all; to compete for a few minutes, to be judged, to be watched, to be inspiring. Lots of National Records with set in various weight classes and age groups. I felt my heart race a little bit more with each record attempt! It was great to be witness to the excellent competition today.

With all that said, I have to take step back for a moment, and really reflect on the time that everyone who has competed and will be competing in Masters Nationals. Hours and hours spent in the gym, away from families, making sacrifices to not miss training sessions, all to compete for a few minutes on a platform. I think that is why I’m so interested in Olympic Weightlifting. I find such stark similarities between Olympic Weightlifting and throwing. In throwing, much lifting weightlifting, athletes spend hundreds of hours training and preparing for a competition that lasts a couple of minutes. If we make the finals in throwing, we receive six throws. In weightlifting you get six attempts. Make a Snatch and a Clean & Jerk and you receive a total. Miss a Snatch and the meet is all but done. If you don’t throw far enough to make the top 8 or 9, you don’t make the finals in throwing. Lots of hard work, sweat, blood, and tears for about 10 seconds of ring time. Believe me, I have been there on multiple occasions. But if you don’t compete against the best and really test yourself, you’ll never know how you’ll compete. Much like today, that is what throwing is like. In no other sport will I be able to compete in the same flight as Olympic throwers. Similar in weightlifting, today I got the chance to watch Daniel Camargo compete. Former US Olympic Training Center resident and elite International weightlifter, Daniel is the owner of Camargos Oly Concepts, an Olympic Weightlifting gym located just outside of Orlando, FL. Coming off of shoulder surgery, Daniel went 6/6 today and won his weight class. Mind you, after coaching some of his athletes in the session immediately before his. I did that on more than one occasion when I was younger, inexperienced, and didn’t know better. Reflecting back now, my athletes suffered so I could have competed. Today, it seemed otherwise for Daniel’s athletes. I’m not sure what he is like not in competition, but his athletes have thus far performed extremely well at Masters Nationals. He definitely figured out a way to coach his athletes to the best of his ability, all while preparing to compete himself, in the hopes of securing a spot on the Masters Worlds team, which he indeed qualified for. To all the lifters and coaches that took the time out of their day to speak with me, thank you! Thank you for competing and for being inspiring. I learned a lot about Olympic Weightlifting today. I learned about support systems, family dynamics, and self-determination. Nobody makes us compete. We have something inside us. Something different. Something that others don’t have. Something others may not understand. They may never understand. What it takes to train hundreds of hours for in order to compete for a couple of minutes. What it means to sacrifice time spent with family and friends to get better at a sport that most people don’t understand. Most importantly, you inspired me and humbled me. Thank you. |

Dr. Charles InfurnaCharles Infurna, Ed.D., is the owner and lead coach of Forza Athletics Track Club. Dr. Infurna has coached National Record Holders, National Champions, All-Americans, and Conference Champions at the Post-Collegiate, Collegiate, and High School level. Archives

January 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed